Most agreements to resolve ethno-national conflicts don’t survive the test of time. A study of those that have succeeded reveals the secret: They sprang from prisons. Israel needs to take this under consideration for the ‘day after’ the war in Gaza

source : Haaretz A summing up is to be found HERE

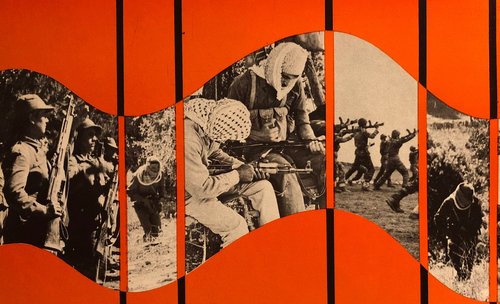

Marwan Barghouti mural in Gaza. He played a key role in drafting the 2006 “prisoners document,” which brought Fatah and Hamas to enter into talks.Credit: Majdi Fathi / ReutersAvraham SelaTomer Schorr-Liebfeld

Jan 25, 2024

The discussion about the “day after” the war in the Gaza Strip necessitates a reexamination of the question of the security prisoners being held by Israel. Not only in the context of an exchange deal in which, it is to be hoped, the Israeli hostages in Hamas captivity will be released in exchange for, among other things, the prisoners incarcerated in Israel; but also in a context that is barely discussed: the role that the Palestinian prisoners can play in shaping the political situation and even in promoting a long-term Israeli-Palestinian settlement.

This has become relevant for two reasons. The first is the political vision set forth by U.S. President Joe Biden in a column this past November in The Washington Post, in which he posited as a strategic aim the establishment of a Palestinian state alongside Israel. According to Biden, it would be governed by a “revitalized” Palestinian Authority, namely one vested with greater political legitimacy and more effective capacity for functioning than the existing PA. That authority would be responsible for governing the Gaza Strip after the vanquishing of Hamas.

The second reason is the urgent need to bring about an efficient system of governance in the Gaza Strip, whose cardinal task will be to rehabilitate and rebuild the administrative and physical infrastructures, which have been utterly devastated. In both of these contexts, Palestinian prisoners can play a role both symbolic and practical.

Already now, before the war has ended, the incomprehensible number of more than 25,000 people have been killed in Gaza; towns, villages, residential neighborhoods and refugee camps have been reduced to rubble; and a humanitarian disaster has been inflicted on the Strip’s two million inhabitants. Even if the international community comes up with the necessary funds, an efficient apparatus will be needed to channel the money into the construction of physical infrastructures and establishment of civilian services, to enforce law and order, and prevent a renewed deterioration into violence, both internally and against Israel.

Rehabilitating the Gaza Strip will be a years-long project, taking place under chaotic social and political conditions. Reason thus leads to the conclusion that no Palestinian government will be able to fulfill its task in the Gaza Strip without the integration of Hamas in a political format. Releasing prisoners in exchange for hostages can be expected to boost Hamas’ prestige in the short term, but it’s likely that in the long run, the mortal blow dealt to its military capabilities and to its leadership in the Strip will weaken the movement and bring about its readiness to take part as a faction within the framework of the PLO, and in partnership with the Fatah-based Palestine Liberation Organization. Indications to that effect on the part of Hamas’ political leadership are already discernible.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s vigorous opposition to Biden’s blueprint is a direct continuation of the policy of separating between the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, which Netanyahu has cultivated since 2009, with the aim of averting the establishment of a Palestinian state. That opposition explains the preference of the security establishment today for a “government of hamulas” (clans) over a central Palestinian authority. This is an untenable conception of governance from every point of view, and one that disregards the rupture of Gaza’s social-political structures wrought by the war.

It’s hardly possible to ignore the weaknesses of the PA and of Mahmoud Abbas, who has headed it since 2005, or to gainsay the need for a reform of the PA’s structure and its personal makeup. However, the PA is the only Palestinian-national framework that can possibly serve as a post-war government in the Gaza Strip. This is not only the view of the West but also of the Arab states, especially those that are likely to donate funds for the Strip’s reconstruction.

One of the most intractable barriers in processes of conflict resolution, as in international humanitarian involvement, is the absence of a central authority that enjoys legitimacy and is vested with enforcement capability. In this context, the release of security prisoners who have committed to abstaining from a return to violence, can bestow political legitimacy domestically on the Palestinian government and bolster its administrative abilities. This, by virtue of their activity on behalf of the national cause, the organizational experience they have gleaned and the broad public support they enjoy among the Palestinian public overall.

Most of the Fatah prisoners who were released before and after the Oslo Accords – among them Marwan Barghouti, Jibril Rajoub, Hisham Abdel Razek, Sufyan Abu Zaydeh and Qadura Fares – unreservedly supported the accords and the principle of establishment of a Palestinian state alongside Israel. They also assumed senior positions in the PA government. Barghouti, who in 2002 was sentenced by Israel to five life terms plus 40 years in prison, is today the only senior Fatah prisoner who has for years enjoyed the broadest support of the Palestinian public. It’s not by chance that he tops the list of the prisoners whose release Hamas is demanding now, perhaps in the hope that he will treat the organization well if and when a reshuffled PA returns to power in the Gaza Strip.

- Mass release of Palestinian security inmates could save Israel billions, but at what risk?

- There’ll only be a Palestinian state if the PLO disengages from Hamas

- Post-war Gaza warrants a fresh approach, but Netanyahu is holding on to old fantasies

Calls for Barghouti’s release are voiced from time to time, and recently more insistently, by left-wingers in Israel, who believe that, like Nelson Mandela in his country, he can lead the Palestinians to a political settlement with Israel. From personal acquaintance with Barghouti in the 1990s (of co-author Sela), it can be surmised that he will be willing to advance a solution in this spirit, but only on condition that the Israeli government is ready to promote such an agreement. Without that readiness on Israel’s part, his release would only serve to further intensify the conflict with the Palestinians.

The idea that the security prisoners being held by Israel can play a key role in forming an effective PA, and more specifically in promoting a political settlement based on President Biden’s principles, is based on a comparative study we conducted on the role of political-security prisoners in the resolution of protracted ethno-national conflicts. Our paper on that study, which was published last November in the International Studies Quarterly, the flagship of the International Studies Association, examined this subject in the context of three different conflicts: Northern Ireland, South Africa and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

The PA is the only Palestinian-national framework that can possibly serve as a post-war government in the Gaza Strip. This is not only the view of the West but also of the Arab states, especially those that are likely to donate funds for the Strip’s reconstruction.

The study points to the disparity between the effective absence of Palestinian prisoners from the Oslo process, and the key role played by prisoners from Northern Ireland and South Africa in resolving those conflicts. In both cases, the prisoners worked to lay the groundwork for negotiations, the ratification of the agreement that emerged, and then its implementation. As such, the agreements reached in Northern Ireland and South Africa differed from most of the accords attained in ethno-national conflicts in the first two decades post-Cold War, which, like the Oslo Accords, reverted to hostilities within a few years of being signed.

Political-security prisoners are not a cause but a consequence of the long conflicts under consideration, but their incarceration generates powerful feelings in their communities, and can potentially shape the future of the conflict in the direction of a settlement or an escalation. The emotional intensity of this subject is reflected in Hamas’ recurring attempts, including in the October 7 attack, to abduct Israeli soldiers and civilians who can then be exchanged for Palestinian prisoners held by Israel. Hence, an intelligent use of the symbolic capital embodied in the prisoner population might contribute much to resolving the conflict, as attested to by the processes undergone in both Northern Ireland and South Africa in this context.

The prisoners of a national struggle are perceived by their public as patriots, and identified with devotion and sacrifice for the sake of the commonality. The story of the longtime prisoners in Israel, like in Northern Ireland and South Africa, paints a similar picture of the prison as a “hothouse of ideas.” It is here that a national consciousness can develop by way of deep and free debate, which includes calling into question basic assumptions and sacrosanct perceptions regarding the national vision and the strategy for realizing it.

In both those countries, the long years of living together in close quarters in prison created a distinct community that expanded voluntarily and informally; together with inmates who had served their terms and were released, these prisoners became, over the years, a key power center in their movements’ decision-making processes. In many cases, the prisoners shaped the agenda of the resistance movement on the outside by staging hunger strikes, which then engendered manifestations of revolt and violence outside the prison. Through the social connections that were forged in the prisons, the prisoners succeeded in promoting their interpretation of reality and in transforming the hegemonic discourse of armed struggle into one of negotiations instead.

The Irish Republican Army inmates in Northern Ireland, for example, laid the groundwork for the political process of the 1980s and early 1990s, initially parallel to the use of violence and later by development of a strategy of nonviolent struggle. Subsequently, they effectively gave up the dream of a united Ireland, postponing it to an indefinite time in the future. At the same time, the Protestant leadership was compelled to accept the true and full sharing of power with the Catholics. During the period between the signing of the agreement in Northern Ireland in April 1998 and its ratification a few weeks later by way of referendums held in the two rival communities, the prisoners carried considerable weight in forming a Catholic consensus around the agreement. Furthermore, in the two fraught years that followed the referendums, they played a central role in curbing the “spoilers” who advocated continued violence, and in preventing backsliding of the communities into the cycle of blood.

The first lesson one can take from Northern Ireland and South Africa is the essential importance of prisoners’ participation in legitimizing various aspects of resolution of the conflict, which by its nature entails bitter concessions, perceived as taboo, on certain issues.

In South Africa, Mandela, and through him the other prisoners and the leadership of the African National Congress, came to terms with giving up the ANC’s aspiration to see the country’s resources redistributed, after being apprised of the apprehensions that guided the behavior of the other side. Similarly, in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, it was the prisoners who were released in the “Jibril deal,” in 1985, who instigated the first intifada and led the PLO leadership, in 1988, to declare an independent Palestinian state on the basis of the United Nations partition resolution of 1947, thereby effectively abandoning the idea of liberating all of Palestine.

In some cases, the prisoners dictated political decisions to their movements. A case in point is the “prisoners’ document” of 2006, which was signed by the jailed leaders of Fatah, Hamas and other organizations in an attempt to end the rift between the PLO-Fatah leadership and Hamas. The document, in whose drafting Marwan Barghouti played a key role, compelled the two rival factions to enter into talks on cooperation on the basis of a platform that accepted the two-states principle. The result was a strategic accord between the factions and the signing of the Mecca Agreement of 2007, even though four months later that concord was voided when Hamas took over the Gaza Strip by force.

The importance of security-political prisoners in efforts to resolve protracted intra-state conflicts stems in large measure from the scope of their sector, which is a consequence of decades of bloody conflict between the state and the group rebelling in society. Thus, in decades of Israeli occupation in the territories, about a million Palestinians have passed through Israeli detention facilities, constituting about 20 percent of the population. In other words, almost every Palestinian family has experienced the incarceration of a family member, neighbor or close acquaintance, so much so that arrest became a formative experience of the whole of Palestinian society. In Northern Ireland and South Africa, the prisoners constituted a smaller though still substantial percentage of the populations.

* * *

The first lesson one can take from the resolution of the conflicts in Northern Ireland and South Africa is the essential importance of prisoners’ participation in legitimizing various aspects of resolution of the conflict, which by its nature entails bitter concessions, perceived as taboo, on certain issues. In Israel, by contrast, the prisoners were not taken into account in any way ahead of the signing of the Oslo Accords. Even afterward, the government consistently objected to the release of prisoners “with blood on their hands,” an approach that weakened the support of the community of prisoners for the entire process.

The second lesson concerns the need for a prior stage in which confidential “feelers” were sent out to prisoner-leaders while they were still incarcerated, even before the start of real negotiations between the sides. These contacts, which in some cases were drawn-out and crisis-ridden, enabled the sides to exhaust fully the negotiating possibilities and to formulate a possible framework for an agreement, even before anything was committed to paper. Whereas in Northern Ireland and South Africa, talks were conducted between government representatives and the prisoners’ leaders for many years before agreements were made, the Oslo Accords were concluded within a short period of just months, and without the leaders of the two sides having had time to examine thoroughly the mutual concessions that they would be required to make even to implement the limited agreement they signed.

The Oslo Accords did in fact represent a vague and not clearly defined blueprint for the strategic goal of the process. Postponing negotiations and decisions on the conflict’s core issues (Jerusalem, refugees, borders, Jewish settlements) to the stage of the final-status negotiations, reflected the fact that there were deep and substantive differences on these issues, which would surface afterward and cause the collapse of the process. Above all, the splitting of the process into two stages exposed it to fierce opposition from both sides. The Palestinian prisoners released after the signing of the Oslo Accords, many of whose comrades remained incarcerated in Israel, were unwilling to grant legitimacy to the process, the more so as it was effectively suspended in the period of the first Netanyahu government (1996-1999).

With the wisdom of hindsight, it’s possible to surmise that a meaningful dialogue with the Palestinian prisoners, who from the outset were exposed to the internal Israeli discourse and enjoyed public influence back home, would have enabled the two sides to get to know each other better, helped them understand the limits of the possible on the other side, and might even have led to a more coherent blueprint for a solution.

The third lesson lies in the importance of reaching agreement on a general amnesty for prisoners who support the accord that is hammered out, and who commit to desisting absolutely from the use of violence. In Northern Ireland and South Africa, a mechanism was worked out for the release of prisoners on just such terms. This helped reduce to a large extent the use of violence by the accord’s opponents, by granting them the possibility of inclusion in the amnesty in return for renouncing violence. As such, the prospect of the prisoners being freed acted as an incentive for all the organizations to join the cease-fire in the most critical period of the agreement’s implementation, when most protracted conflicts slide back into violence.

* * *

Beyond formulation of a political blueprint for the postwar period being a clear American demand, it is also a supreme Israeli interest from both the security and political viewpoints. It is essential for Israel that an effective Palestinian governing institution be established in Gaza in place of Hamas. Moreover, the rehabilitation of life in the Gaza Strip following the physical destruction and the humanitarian crisis caused by the war, is a vital element in creation of a secure border with Israel. In both matters, the international community will play a decisive role, which will in turn obligate the government of Israel to make tough political concessions.

Launching a direct dialogue with the prisoners obligates a conceptual shift by decision makers and other public leaders in Israel – most of whom view the prisoners as terrorist murderers who must serve out their punishments in full.

Israel has the possibility of correcting its approach to the issue of the prisoners, if it wishes to turn over a new leaf in the conflict with the Palestinians. Indeed, the veteran inmates from Fatah are not lovers of Zion, and their support for a settlement on the basis of “two states for two peoples” reflects an acquiescence to the limits of power and an acceptance of reality. Many of them have been incarcerated for decades in Israeli prisons and are fluent in Hebrew and knowledgeable about the history of the State of Israel and about its social and political situation. At the same time, no one need expect that they will make concessions on substantive questions relating to core issues, such as have been put forward by the PLO in the years since the Oslo Accords.

Launching a direct dialogue with the prisoners obligates a conceptual shift by decision makers and other public leaders in Israel – most of whom view the prisoners as terrorist murderers who must serve out their punishments in full. It is self-evident that a necessary condition for holding a dialogue of this kind is readiness by Israel to renew the negotiations on a two-state basis, which according to Biden is “the only way to ensure the long-term security of both the Israeli and Palestinian people” and which is now “more imperative than ever.” In this context we should bear in mind Yitzhak Rabin’s assertion that, “The road to reconciliation leads through the prisons.”

If and when the government of Israel is ready to discuss sincerely the two-state blueprint with the Palestinians, it will do well to adopt the models of Northern Ireland and South Africa on this issue, and begin a dialogue with Barghouti and perhaps with members of other Palestinian organizations while they are still in prison. Doing so will help prepare the ground for their participation in rebuilding the Palestinian Authority, in a way that will gain it broad public support and enable it to function as an effective governmental body. As such, the freeing of the prisoners will be an integral element of a future settlement and make the prisoners practical partners in its acceptance and implementation.

The war to eradicate Hamas rule in the Gaza Strip has restored to the top of the regional and international agenda the “unfinished business” of a resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. What began with the signing of the Declaration of Principles between the Rabin government and the PLO in September 1993 never even achieved its minimal goals: full autonomy for the Palestinians in most of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Even if the renewal of the negotiations with the Palestinians on the two-state blueprint is anathema to the majority of the Israeli public today, the crisis into which Israel was plunged on October 7 emphasizes the necessity of fully exhausting that process.

Tomer Schorr-Liebfeld’s doctoral dissertation, submitted to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 2021, is about political prisoners in conflict-resolution processes. Avraham Sela is emeritus professor in the Department of International Relations and a senior research fellow in the Truman Research Institute for the Advancement of Peace, both at the Hebrew University.

WORKERS OF THE UNITED NATIONS RELIEF AND WORKS AGENCY FOR PALESTINE REFUGEES (UNRWA) PREPARE MEDICAL AID FOR DISTRIBUTION TO SHELTERS, DEIR AL-BALAH, NOVEMBER 4, 2023. (PHOTO: SULIMAN EL-FARA/APA IMAGES)

WORKERS OF THE UNITED NATIONS RELIEF AND WORKS AGENCY FOR PALESTINE REFUGEES (UNRWA) PREPARE MEDICAL AID FOR DISTRIBUTION TO SHELTERS, DEIR AL-BALAH, NOVEMBER 4, 2023. (PHOTO: SULIMAN EL-FARA/APA IMAGES)

![Palestinians forever changed by Israeli torture Nour Alyan, 27, who says he was held in stress positions for hours while in Israeli detention, displays the paperwork from his five separate arrests [Edmee Van Rijn/Al Jazeera]](https://i0.wp.com/www.aljazeera.com/mritems/imagecache/mbdxxlarge/mritems/Images/2016/4/2/6c4ec1fd57d14e88ae8e7add3cd9b63c_18.jpg)