Israeli soldiers describe the near-total absence of firing regulations in the Gaza war, with troops shooting as they please, setting homes ablaze, and leaving corpses on the streets — all with their commanders’ permission.

ByOren ZivJuly 8, 2024

ByOren ZivJuly 8, 2024

In partnership with

In early June, Al Jazeera aired a series of disturbing videos revealing what it described as “summary executions”: Israeli soldiers shooting dead several Palestinians walking near the coastal road in the Gaza Strip, on three separate occasions. In each case, the Palestinians appeared unarmed and did not pose any imminent threat to the soldiers.

Such footage is rare, due to the severe constraints faced by journalists in the besieged enclave and the constant danger to their lives. But these executions, which did not appear to have any security rationale, are consistent with the testimonies of six Israeli soldiers who spoke to +972 Magazine and Local Call following their release from active duty in Gaza in recent months. Corroborating the testimonies of Palestinian eyewitnesses and doctors throughout the war, the soldiers described being authorized to open fire on Palestinians virtually at will, including civilians.

The six sources — all except one of whom spoke on the condition of anonymity — recounted how Israeli soldiers routinely executed Palestinian civilians simply because they entered an area that the military defined as a “no-go zone.” The testimonies paint a picture of a landscape littered with civilian corpses, which are left to rot or be eaten by stray animals; the army only hides them from view ahead of the arrival of international aid convoys, so that “images of people in advanced stages of decay don’t come out.” Two of the soldiers also testified to a systematic policy of setting Palestinian homes on fire after occupying them.

Several sources described how the ability to shoot without restrictions gave soldiers a way to blow off steam or relieve the dullness of their daily routine. “People want to experience the event [fully],” S., a reservist who served in northern Gaza, recalled. “I personally fired a few bullets for no reason, into the sea or at the sidewalk or an abandoned building. They report it as ‘normal fire,’ which is a codename for ‘I’m bored, so I shoot.’”

Since the 1980s, the Israeli military has refused to disclose its open-fire regulations, despite various petitions to the High Court of Justice. According to political sociologist Yagil Levy, since the Second Intifada, “the army has not given soldiers written rules of engagement,” leaving much open to the interpretation of soldiers in the field and their commanders. As well as contributing to the killing of over 38,000 Palestinians, sources testified that these lax directives were also partly responsible for the high number of soldiers killed by friendly fire in recent months.

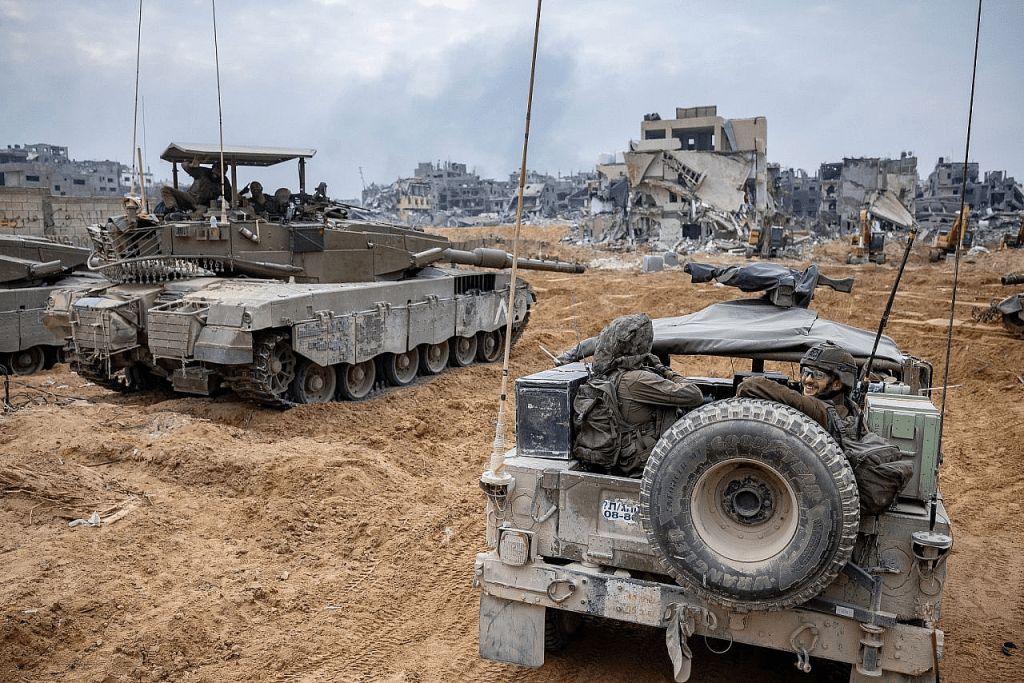

Israeli soldiers from the 8717 Battalion of the Givati Brigade operating in Beit Lahia, in the northern Gaza Strip, during a military operation, December 28, 2023. (Yonatan Sindel/Flash90)

“There was total freedom of action,” said B., another soldier who served in the regular forces in Gaza for months, including in his battalion’s command center. “If there is [even] a feeling of threat, there is no need to explain — you just shoot.” When soldiers see someone approaching, “it is permissible to shoot at their center of mass [their body], not into the air,” B. continued. “It’s permissible to shoot everyone, a young girl, an old woman.”

B. went on to describe an incident in November when soldiers killed several civilians during the evacuation of a school close to the Zeitoun neighborhood of Gaza City, which had served as a shelter for displaced Palestinians. The army ordered the evacuees to exit to the left, toward the sea, rather than to the right, where the soldiers were stationed. When a gunfight erupted inside the school, those who veered the wrong way in the ensuing chaos were immediately fired at.

“There was intelligence that Hamas wanted to create panic,” B. said. “A battle started inside; people ran away. Some fled left toward the sea, [but] some ran to the right, including children. Everyone who went to the right was killed — 15 to 20 people. There was a pile of bodies.”

‘People shot as they pleased, with all their might’

B. said that it was difficult to distinguish civilians from combatants in Gaza, claiming that members of Hamas often “walk around without their weapons.” But as a result, “every man between the ages of 16 and 50 is suspected of being a terrorist.”

“It is forbidden to walk around, and everyone who is outside is suspicious,” B. continued. “If we see someone in a window looking at us, he is a suspect. You shoot. The [army’s] perception is that any contact [with the population] endangers the forces, and a situation must be created in which it is forbidden to approach [the soldiers] under any circumstances. [The Palestinians] learned that when we enter, they run away.”

Even in seemingly unpopulated or abandoned areas of Gaza, soldiers engaged in extensive shooting in a procedure known as “demonstrating presence.” S. testified that his fellow soldiers would “shoot a lot, even for no reason — anyone who wants to shoot, no matter what the reason, shoots.” In some cases, he noted, this was “intended to … remove people [from their hiding places] or to demonstrate presence.”

M., another reservist who served in the Gaza Strip, explained that such orders would come directly from the commanders of the company or battalion in the field. “When there are no [other] IDF forces [in the area] … the shooting is very unrestricted, like crazy. And not just small arms: machine guns, tanks, and mortars.”

Even in the absence of orders from above, M. testified that soldiers in the field regularly take the law into their own hands. “Regular soldiers, junior officers, battalion commanders — the junior ranks who want to shoot, they get permission.”

S. remembered hearing over the radio about a soldier stationed in a protective compound who shot a Palestinian family walking around nearby. “At first, they say ‘four people.’ It turns into two children plus two adults, and by the end it’s a man, a woman, and two children. You can assemble the picture yourself.”

Only one of the soldiers interviewed for this investigation was willing to be identified by name: Yuval Green, a 26-year-old reservist from Jerusalem who served in the 55th Paratroopers Brigade in November and December last year (Green recently signed a letter by 41 reservists declaring their refusal to continue serving in Gaza, following the army’s invasion of Rafah). “There were no restrictions on ammunition,” Green told +972 and Local Call. “People were shooting just to relieve the boredom.”

Green described an incident that occurred one night during the Jewish festival of Hanukkah in December, when “the whole battalion opened fire together like fireworks, including tracer ammunition [which generates a bright light]. It made a crazy color, illuminating the sky, and because [Hannukah] is the ‘festival of lights,’ it became symbolic.”

Israeli soldiers from the 8717 Battalion of the Givati Brigade operating in Beit Lahia, northern Gaza Strip, December 28, 2023. (Yonatan Sindel/Flash90)

C., another soldier who served in Gaza, explained that when soldiers heard gunshots, they radioed in to clarify whether there was another Israeli military unit in the area, and if not, they opened fire. “People shot as they pleased, with all their might.” But as C. noted, unrestricted shooting meant that soldiers are often exposed to the huge risk of friendly fire — which he described as “more dangerous than Hamas.” “On multiple occasions, IDF forces fired in our direction. We didn’t respond, we checked on the radio, and no one was hurt.”

At the time of writing, 324 Israeli soldiers have been killed in Gaza since the ground invasion began, at least 28 of them by friendly fire according to the army. In Green’s experience, such incidents were the “main issue” endangering soldiers’ lives. “There was quite a bit [of friendly fire]; it drove me crazy,” he said.

For Green, the rules of engagement also demonstrated a deep indifference to the fate of the hostages. “They told me about a practice of blowing up tunnels, and I thought to myself that if there were hostages [in them], it would kill them.” After Israeli soldiers in Shuja’iyya killed three hostages waving white flags in December, thinking they were Palestinians, Green said he was angry, but was told “there’s nothing we can do.” “[The commanders] sharpened procedures, saying ‘You have to pay attention and be sensitive, but we are in a combat zone, and we have to be alert.’”

B. confirmed that even after the mishap in Shuja’iyya, which was said to be “contrary to the orders” of the military, the open-fire regulations did not change. “As for the hostages, we didn’t have a specific directive,” he recalled. “[The army’s top brass] said that after the shooting of the hostages, they briefed [soldiers in the field]. [But] they didn’t talk to us.” He and the soldiers who were with him heard about the shooting of the hostages only two and a half weeks after the incident, after they left Gaza.

“I’ve heard statements [from other soldiers] that the hostages are dead, they don’t stand a chance, they have to be abandoned,” Green noted. “[This] bothered me the most … that they kept saying, ‘We’re here for the hostages,’ but it is clear that the war harms the hostages. That was my thought then; today it turned out to be true.”

Israeli soldiers from the 8717 Battalion of the Givati Brigade operating in Beit Lahia, in the northern Gaza Strip, December 28, 2023. (Yonatan Sindel/Flash90)

‘A building comes down, and the feeling is, “Wow, what fun”’

A., an officer who served in the army’s Operations Directorate, testified that his brigade’s operations room — which coordinates the fighting from outside Gaza, approving targets and preventing friendly fire — did not receive clear open-fire orders to transmit to soldiers on the ground. “From the moment you enter, at no point is there a briefing,” he said. “We didn’t receive instructions from higher up to pass on to the soldiers and battalion commanders.”

He noted that there were instructions not to shoot along humanitarian routes, but elsewhere, “you fill in the blanks, in the absence of any other directive. This is the approach: ‘If it is forbidden there, then it is permitted here.’”

A. explained that shooting at “hospitals, clinics, schools, religious institutions, [and] buildings of international organizations” required higher authorization. But in practice, “I can count on one hand the cases where we were told not to shoot. Even with sensitive things like schools, [approval] feels like only a formality.”

In general, A. continued, “the spirit in the operations room was ‘Shoot first, ask questions later.’ That was the consensus … No one will shed a tear if we flatten a house when there was no need, or if we shoot someone who we didn’t have to.”

A. said he was aware of cases in which Israeli soldiers shot Palestinian civilians who entered their area of operation, consistent with a Haaretz investigation into “kill zones” in areas of Gaza under the army’s occupation. “This is the default. No civilians are supposed to be in the area, that’s the perspective. We spotted someone in a window, so they fired and killed him.” A. added that it often was not clear from the reports whether soldiers had shot militants or unarmed civilians — and “many times, it sounded like someone was caught up in a situation, and we opened fire.”

But this ambiguity about the identity of victims meant that, for A., military reports about the numbers of Hamas members killed could not be trusted. “The feeling in the war room, and this is a softened version, was that every person we killed, we counted him as a terrorist,” he testified.

“The aim was to count how many [terrorists] we killed today,” A. continued. “Every [soldier] wants to show that he’s the big guy. The perception was that all the men were terrorists. Sometimes a commander would suddenly ask for numbers, and then the officer of the division would run from brigade to brigade going through the list in the military’s computer system and count.”

A.’s testimony is consistent with a recent report from the Israeli outlet Mako, about a drone strike by one brigade that killed Palestinians in another brigade’s area of operation. Officers from both brigades consulted on which one should register the assassinations. “What difference does it make? Register it to both of us,” one of them told the other, according to the publication.

During the first weeks after the Hamas-led October 7 attack, A. recalled, “people were feeling very guilty that this happened on our watch,” a feeling that was shared among the Israeli public writ large — and quickly transformed into a desire for retribution. “There was no direct order to take revenge,” A. said, “but when you reach decision junctures, the instructions, orders, and protocols [regarding ‘sensitive’ cases] only have so much influence.”

When drones would livestream footage of attacks in Gaza, “there were cheers of joy in the war room,” A. said. “Every once in a while, a building comes down … and the feeling is, ‘Wow, how crazy, what fun.’”

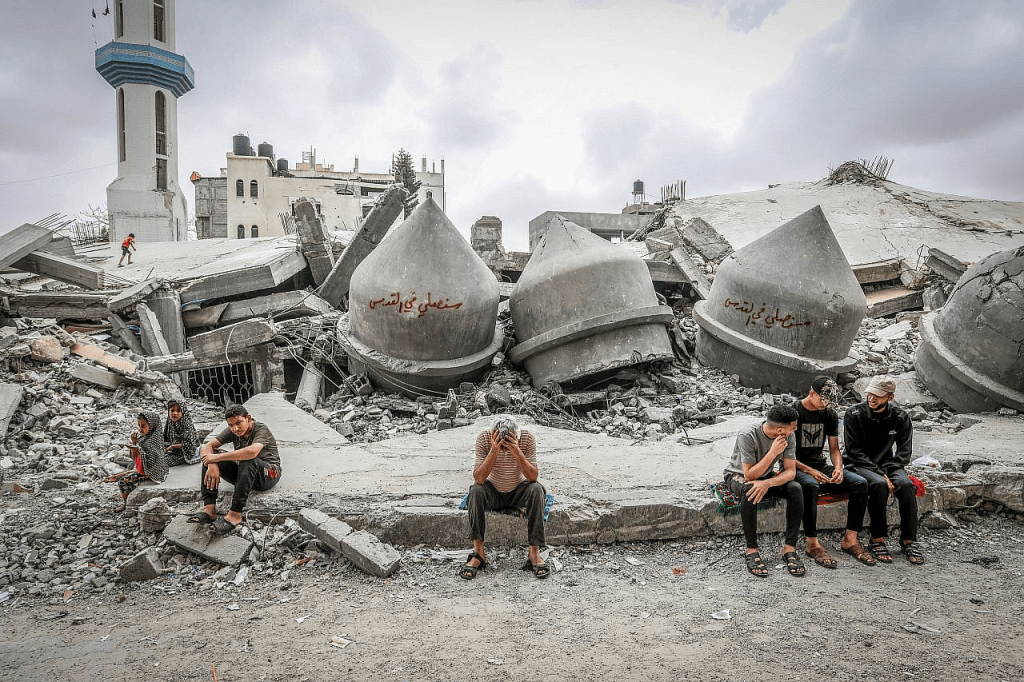

Palestinians at the site of a mosque destroyed in an Israeli airstrike, near the Shaboura refugee camp in Rafah, southern Gaza Strip, April 26, 2024. (Abed Rahim Khatib/Flash90)

A. noted the irony that part of what motivated Israelis’ calls for revenge was the belief that Palestinians in Gaza rejoiced in the death and destruction of October 7. To justify abandoning the distinction between civilians and combatants, people would resort to such statements as “‘They handed out sweets,’ ‘They danced after October 7,’ or ‘They elected Hamas’ … Not everyone, but also quite a few, thought that today’s child [is] tomorrow’s terrorist.

“I, too, a rather left-wing soldier, forget very quickly that these are real homes [in Gaza],” A. said of his experience in the operations room. “It felt like a computer game. Only after two weeks did I realize that these are [actual] buildings that are falling: if there are inhabitants [inside], then [the buildings are collapsing] on their heads, and even if not, then with everything inside them.”

‘A horrific smell of death’

Multiple soldiers testified that the permissive shooting policy has enabled Israeli units to kill Palestinian civilians even when they are identified as such beforehand. D., a reservist, said that his brigade was stationed next to two so-called “humanitarian” travel corridors, one for aid organizations and one for civilians fleeing from the north to the south of the Strip. Within his brigade’s area of operation, they instituted a “red line, green line” policy, delineating zones where it was forbidden for civilians to enter.

According to D., aid organizations were permitted to travel into these zones with prior coordination (our interview was conducted before a series of Israeli precision strikes killed seven World Central Kitchen employees), but for Palestinians it was different. “Anyone who crossed into the green area would become a potential target,” D. said, claiming that these areas were signposted to civilians. “If they cross the red line, you report it on the radio and you don’t need to wait for permission, you can shoot.”

Yet D. said that civilians often came into areas where aid convoys passed through in order to look for scraps that might fall from the trucks; nonetheless, the policy was to shoot anyone who tried to enter. “The civilians are clearly refugees, they are desperate, they have nothing,” he said. Yet in the early months of the war, “every day there were two or three incidents with innocent people or [people] who were suspected of being sent by Hamas as spotters,” whom soldiers in his battalion shot.

The soldiers testified that throughout Gaza, corpses of Palestinians in civilian clothes remained scattered along roads and open ground. “The whole area was full of bodies,” said S., a reservist. “There are also dogs, cows, and horses that survived the bombings and have nowhere to go. We can’t feed them, and we don’t want them to get too close either. So, you occasionally see dogs walking around with rotting body parts. There is a horrific smell of death.”

Rubbles of houses destroyed by Israeli airstrikes in the Jabalia area in the northern Gaza Strip, October 11, 2023. (Atia Mohammed/Flash90)

But before the humanitarian convoys arrive, S. noted, the bodies are removed. “A D-9 [Caterpillar bulldozer] goes down, with a tank, and clears the area of corpses, buries them under the rubble, and flips [them] aside so that the convoys don’t see it — [so that] images of people in advanced stages of decay don’t come out,” he described.

“I saw a lot of [Palestinian] civilians – families, women, children,” S. continued. “There are more fatalities than are reported. We were in a small area. Every day, at least one or two [civilians] are killed [because] they walked in a no-go area. I don’t know who is a terrorist and who is not, but most of them did not carry weapons.”

Green said that when he arrived in Khan Younis at the end of December, “We saw some indistinct mass outside a house. We realized it was a body; we saw a leg. At night, cats ate it. Then someone came and moved it.”

A non-military source who spoke to +972 and Local Call after visiting northern Gaza also reported seeing bodies strewn around the area. “Near the army compound between the northern and southern Gaza Strip, we saw about 10 bodies shot in the head, apparently by a sniper, [seemingly while] trying to return to the north,” he said. “The bodies were decomposing; there were dogs and cats around them.”

“They don’t deal with the bodies,” B. said of the Israeli soldiers in Gaza. “If they’re in the way, they get moved to the side. There’s no burial of the dead. Soldiers stepped on bodies by mistake.”

Last month, Guy Zaken, a soldier who operated D-9 bulldozers in Gaza, testified before a Knesset committee that he and his crew “ran over hundreds of terrorists, dead and alive.” Another soldier he served with subsequently committed suicide.

‘Before you leave, you burn down the house’

Two of the soldiers interviewed for this article also described how burning Palestinian homes has become a common practice among Israeli soldiers, as first reported in depth by Haaretz in January. Green personally witnessed two such cases — the first an independent initiative by a soldier, and the second by commanders’ orders — and his frustration with this policy is part of what eventually led him to refuse further military service.

When soldiers occupied homes, he testified, the policy was “if you move, you have to burn down the house.” Yet for Green, this made no sense: in “no scenario” could the middle of the refugee camp be part of any Israeli security zone that might justify such destruction. “We are in these houses not because they belong to Hamas operatives, but because they serve us operationally,” he noted. “It is a house of two or three families — to destroy it means they will be homeless.

“I asked the company commander, who said that no military equipment [could be] left behind, and that we did not want the enemy to see our fighting methods,” Green continued. “I said I would do a search [to make sure] there was no [evidence of] combat methods left behind. [The company commander] gave me explanations from the world of revenge. He said they were burning them because there were no D-9s or IEDs from an engineering corp [that could destroy the house by other means]. He received an order and it didn’t bother him.”

“Before you leave, you burn down the house — every house,” B. reiterated. “This is backed up at the battalion commander level. It’s so that [Palestinians] won’t be able to return, and if we left behind any ammunition or food, the terrorists won’t be able to use it.”

Before leaving, soldiers would pile up mattresses, furniture, and blankets, and “with some fuel or gas cylinders,” B. noted, “the house burns down easily, it’s like a furnace.” At the beginning of the ground invasion, his company would occupy houses for a few days and then move on; according to B., they “burned hundreds of houses. There were cases where soldiers set a floor alight, and other soldiers were on a higher floor and had to flee through the flames on the stairs or choked on smoke.”

Green said the destruction the military has left in Gaza is “unimaginable.” At the beginning of the fighting, he recounted, they were advancing between houses 50 meters from each other, and many soldiers “treated the houses [like] a souvenir shop,” looting whatever their residents hadn’t managed to take with them.

Most read on +972

‘Lavender’: The AI machine directing Israel’s bombing spree in Gaza

By failing to stop the Gaza genocide, the ICJ is working exactly as intended

What can Palestinian artists do in the face of our slaughter?