By James Reynolds BBC News in southern Turkey

By James Reynolds BBC News in southern Turkey

The world still blinks every time that Bashar Al Assad speaks, as if it has not learnt anything from 21 months of violence.

In his speech yesterday – his ninth since the uprising began – the dictator offered a plan that would include a lengthy, complicated process of gradual change and “truth and reconciliation”. That would, in theory, lead to a new coalition government and a new constitution.

The speech was preceded by an aggressive two-week diplomatic campaign by the regime’s allies and the UN envoy Lakhdar Brahimi. That renewed push for diplomacy followed 140 countries’ recognition of the National Coalition as the sole representative of the Syrian people, Nato Patriot missiles and military personnel that were dispatched to Turkey’s border, and pledges of increased support for the opposition.

The diplomatic overture by the regime is part of a Russian-backed plan that would keep Al Assad in power until presidential elections in the summer of 2014. And the diplomacy appears to have succeeded in slowing down aid to the rebels, with reports that arms supplies are drying up. But the speech yesterday should remind the world that this dictator has no place in a future Syria and that support for the rebels is the only way forward.

Russia probably pressured on Al Assad to announce a plan of reconciliation. But the speech sounded more vindictive, dismissive and exclusivist than even his previous bombast. For example, he said the plan was directed at only segments of the opposition, and that “those who reject the offer, I say to them: why would you reject an offer that was not meant for you in the first place?” In other points, he emphasised vengeance rather than reconciliation. He also blamed the rebels for the destruction of infrastructure and for cutting off electricity and communications.

“Syria accepts advice but never accepts orders,” he said. “All of what you heard in the past in terms of plans and initiatives were soap bubbles, just like the [Arab] Spring.”

It was clear that he tried to sound steadfast, but his voice betrayed him several times. And before his departure from the room, the crowds chanted “may God protect you” – a chant that is used when someone is threatened. The usual party line is “with our soul and blood, we sacrifice ourselves for you”.

Why would the regime offer a plan now, when it has not made a single meaningful concession since the beginning of the uprising? The violence would never have reached such staggering levels had Al Assad offered reasonable reforms from the beginning. Any hope that he can engineer an end to the violence is an illusion, which will only prolong and worsen the crisis. If anything, the speech showed that the regime will not change its policies except under duress.

The aim seemed to be threefold: to create the impression that the rebels refuse political settlements; to add to the world’s reluctance about arming the rebels; and to question the legitimacy of the National Coalition as the sole representative of the Syrian people.

The proposal of a new constitution is merely a red herring. Syrians did not rise up against the constitution, nor have they demanded constitutional change. People rose up against brutality, and the fact that the existing constitution was never honoured – the mukhabarat apparatus has dominated almost every aspect of Syrian life. The immediate cause of the uprising in Deraa was the mukhabarat, who arrested and tortured school boys for writing anti-regime graffiti and then humiliated their families.

Nor did Syrians rise up to be included in a coalition government. Any government that includes these same criminals will be no different.

and Part II

[youtube http://youtu.be/aXrKukKtHvw?]Jan 1st 2012, 15:23 by A.B. | LONDON

ALASTAIR SMITH is professor of politics at New York University. The recipient of three grants from the National Science Foundation and author of three books, he was chosen as the 2005 Karl Deutsch Award winner, given biennially to the best international-relations scholar under the age of 40. He is co-author of “The Dictator’s Handbook: How Bad Behaviour is Almost Always Good Politics” (2011).

To whom do your guidelines apply?

Everyone. It doesn’t matter whether you are a dictator, a democratic leader, head of a charity or a sports organisation, the same things go on. Firstly, you don’t rule by yourself—you need supporters to keep you there, and what determines how you best survive is how many supporters you have and how big a pool you can draw these supporters from.

Do they actually have to support me, or can I just terrify them into supporting me by threatening them with death?

No, they absolutely have to support you on some level. You can’t personally go around and terrorise everyone. Our poor old struggling Syrian president is not personally killing people on the streets. He needs the support of his family, senior generals who are willing to go out and kill people on his behalf. The common misconception is that you need support from the vast majority of the population, but that’s typically not true. There is all this protest on Wall Street, but CEOs are keeping the people they need to keep happy happy—the members of the board, senior management and a few key investors—because they are the people who can replace them. Protesters on Wall Street have no ability to remove the CEOs. So in a lot of countries the masses are terrified but the supporters are not.

What about Stalin? Even his inner circle was terrified.

Well, the brilliance of the Soviet regime was not just that you relied on few people, but that there were lots of replacements. In a tsarist system you have to rely only on aristocrats, but in a Soviet system everyone can be your supporter. This puts your core circle on notice that they are easily replaced. That, of course, made them horribly loyal. The Mob are very good at this.

Suggested viewing: “On The Waterfront” (1954)

This sounds typically mammalian to me—just groups of gorillas with a silverback?

It is virtually impossible to find any example where leaders are not acting in their own self interest. If you are a democrat you want to gerrymander districts and have an electoral college. This vastly reduces the number of votes a president needs to win an election. Then tax very highly. It’s much better to decide who gets to eat than to let the people feed themselves. If you lower taxes people will do more work, but then people will get rewards that aren’t coming through you. Everything good must come through you. Look at African farm subsidies. The government buys crops at below market price by force. This is a tax on farmers who then can’t make a profit. So, how do you reward people? The government subsidises fertilisers and hands it back that way. In Tanzania vouchers for fertilisers are handed out not to the most productive areas but to the party loyalist areas. This is always subject to the constraint that if you tax too highly people won’t work. This is the big debate in the US. The Republicans are saying that the Democrats have too many taxes and want to suppress workers. But when they were in power five years ago they had no problem with taxing and spending policies, but now it’s taxing their supporters to reward Democrats.

Suggested reading: “Markets and States in Tropical Africa: The Political Basis of Agricultural Policy” by Robert Bates (2005)

Okay. So, I have a small group of rewarded cronies and a highly taxed population. Now what?

Don’t pay your supporters too much! You don’t want them saving up and forming their own power base. Also, don’t be nice to the people at the expense of your coalition. A classic example is natural disasters. Than Shwe was the ruler of Burma when Cyclone Nargis hit in 2008, and he did nothing to help the people. The Generals didn’t warn anybody; though they knew it was coming, they provided virtually no emergency protection. He sent the army in to prevent the people from leaving the flooded Delta areas. He was the perfect example of a leader who never made the mistake of putting the people’s welfare above himself and his coalition.

But what if you really are trying to work for the common good? Is there no way of doing that?

None. If you’re working for the common good you didn’t come to power in the first place. If you’re not willing to cheat, steal, murder and bribe then you don’t come to power.

What if you’re Lech Walesa?

I’m pretty certain he had his own political power base. He wanted to make society more inclusive. This is always the battle cry of revolutionary leaders. When they get into power they change their tune. The real question is what stops politicians from backsliding once they get in? Typically, it’s that the country is broke and the only way you can get people to work is by empowering them socially, but once you do that it becomes hard to take powers back from them. Broke countries are the ones that end up having the political reforms that make them nice places with good economic policy in the long run. Places where there is oil, like Libya, have a very low chance of having democracy. The leaders don’t really need the people to pay the bills of their cronies, because they have oil.

Suggested reading: Anything by Ryszard Kapuściński, a Soviet Polish journalist

Surely Google and Facebook aren’t run like this?

Absolutely they are. All corporations are run like this. The bonuses are handed out to the people who determine the fate of the CEO. It’s a tiny number of people—ten to 20. There are very few shareholder revolts that work. Most leaders are deposed internally. This is why corporations pay huge bonuses.

Don’t I need a cult of personality for my dictatorship?

That’s window dressing. It’s useful in identifying whose side people are on. If you act crazy and the people tell you you’re crazy then they’re not as loyal as you might think. My co-author, Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, and I have a very cynical view, but we think cynicism doesn’t mean it’s not true. It’s not possible to reform a system by imploring people to do the right thing. You have to know how it works. Dictators already know how to be dictators—they are very good at it. We want to point out how they do it so that it’s possible to think about reforms that can actually have meaningful consequences.

Amal Hanano

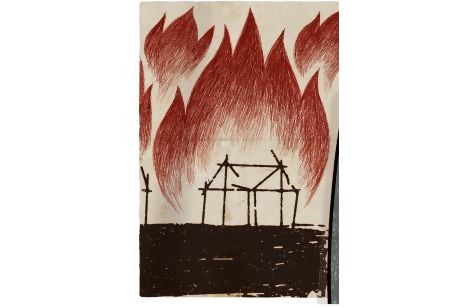

On New Year’s Eve, while the world counted down the minutes until 2013, celebrating with loud blasts of fireworks in the sky, a tent with seven sleeping children and a mother in the Olive Tree refugee camp near the Syrian village of Atmeh burst into flames. On the first day of the new year, five of the children were dead.

The children moved through the camp in groups, some carrying olive tree branches for firewood, others gathered around their mothers who were cooking weed-like greens picked from the land to supplement the dinner rations that are never enough to feed the families. Most are not dressed warmly enough for the cold and almost none of them still go to school. People in the camp that day told me over and over: “We left our homes for our children.” But looking at the underfunded, muddy camp with its open sewers and lack of basic services, you wonder what kind of home this is for a child?

The women were busy at the tent entrances, some cooking, some tending to infants, and others clipping wet, drab clothes onto lines stretched between the tents. A woman named Manar, dressed in her only outfit, a rust-coloured velvet galabiyeh, invited me inside to tell me the story of a fire that had happened just 15 days before.

I ducked into her tent and sat on the concrete blocks that separated the muddy entrance from the sparse interior with a few thin mattresses and blankets piled in the corner. Manar is only in her twenties but looks older, worn out. Her eyes filled with tears as she began, “What should I tell you? My heart is burnt, my heart is burnt. Everything I had was burnt.”

Two weeks ago, Manar left her two sleeping children, five-year-old daughter Fatima and three-year-old son Diya’, in the tent while she trekked to the women’s bathrooms across the camp. A few minutes later, on her way back, she saw clouds of smoke rising from her row and realised her tent had caught fire from a candle she had left burning inside. “I ran barefoot to the tent screaming, ‘My children, my children.’ The people didn’t let me inside. Within five minutes the smouldering tent had melted onto the ground. A man named Abdallah wrapped my son in his jacket. Pieces of my son’s skin are still on the fabric.”

The camp’s director, Yakzan Shishakly, later told me that Manar’s son was taken for emergency care in Turkey before he died the next day. Her daughter perished immediately.

Manar spoke slowly through her tears, holding her small Nokia phone in her hands, clicking between five photographs: two of her son, one of her daughter, and an image of each of their small graves. She paused between the images, crying, stroking, remembering.

“I fled with them here from so far away to be safe. We fled our home in Binnish because of the shelling. They were my entire life. I don’t care about my life any more. I lost my home, my children, my possessions, what’s left to lose? All I have is dirt; no Diya’ and no Fatima.”

Manar’s husband, who has left her alone in the camp, now wants to sell her phone for extra cash. She said, “The phone is my life. I won’t give him the memory card, I’m going to save the card and buy a new phone. If I don’t see them every day I’ll go crazy.”

She pointed to the children who had followed us inside the tent and said, “The entire camp reminds me of my children. I just want people to take care of these children. I lost my children but I don’t want any mother to lose hers. But the children here are dying a thousand deaths every day from cold and hunger.” Another woman in the tent said, “We don’t want the night to come because of the cold. The children fight over the blankets as they sleep. We wish the night would never come.”

Misery in the refugee camps inside Syria is a fact of life for thousands who decided this harsh life is better than living under the regime’s continuous shelling and air strikes that hit their villages. But as the second cold winter of the revolution sets in, lack of basic necessities and medical services in the camps is taking a toll on the refugees, especially the thousands of children. Illnesses such as hepatitis B and tuberculosis are spreading due to severe medicine and vaccine shortages. At least two infants died last month from hypothermia in the Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan. And in the Olive Tree camp in Atmeh, tent fires seem to be one of the grave threats facing the children who are left trapped in the flames.

Shishakly, who founded the Maram Foundation to support the Olive Tree camp, understands that the only way to stop these tent-fire tragedies is to replace all the existing tents with fire-resistant ones. This is the short-term solution that must be implemented along with other safety measures and awareness campaigns. But as the world watches Syria and wrings its hands over our endless tragedies, it is clear that the solution for these camps is simple: people need to go back home.

An image of two scorched children from the New Year’s Eve fire was widely circulated on social media platforms. The small children’s bodies were covered with brown, peeling skin, frozen in their last pose; their facial features melted onto their skulls. I wondered if these two little boys were smiling in one of my photographs from the day before, when they were still alive. Did they sing between the olive trees with their friends as I watched? Did they follow me shyly as we walked through the rows of tents? Were they among the children who asked me to write their names in English in my notebook, delighted to see their names recorded on paper in a foreign language? I’ll never know. I imagine the parents have become even more jaded then they were when I saw them; more weary, more hardened.

Our children live on in the memory cards of cell phones. Their mothers’ loving hands caress the tiny glowing squares in disbelief. Smiling faces are now a distant memory, the battery drains, the faces fade away, and the mothers are left alone in a cold dark tent tortured with heavy questions of guilt. What if I hadn’t left them? What if I had snuffed out the candle and left them in the dark instead? What if we had never left our home?

Are these the choices of Syrians today? To let your child freeze instead of burn? To starve instead of die of illness? To be shelled instead of becoming a refugee? For Manar and the other mothers, it was their fate for their children to burn alive in the final hours of a devastating year between the olive trees. And to live forever in cell phones.

For more information on the Olive Tree refugee camp in Atmeh, Syria, please visit maramfoundation.org

Amal Hanano is the pseudonym for a Syrian American writer

On Twitter: @amalhanano

Latest on Syria

Syria mixed chemicals at two storage sites at the end of November 2012 and filled dozens of bombs, likely with sarin nerve gas, and loaded them onto vehicles near air bases according to anonymous U.S. military, intelligence, and diplomatic officials.

A public warning by President Obama, and private messages from Russia, Iraq, Turkey, and possibly Jordan coerced Syria to stop the chemical and bomb preparation. However, officials say the weapons are still in storage near Syrian air bases, and could be deployed in between two and six hours for use by President Bashar al-Assad.

Meanwhile, on Tuesday the United Nations’ World Food Program (WFP) said it is unable to provide assistance to 1 million Syrians who are going hungry due to the 22-month-long conflict. According to spokeswoman Elisabeth Byrs, the agency aims to help 1.5 million of the 2.5 million Syrians in need. It is not able to reach all the people requiring help because of continued fighting and the lack of access to the port of Tartus, where it had to remove its staff. The program also had to pull its staff from offices in Homs, Aleppo, and Qamisly.

Additionally, the U.N. refugee agency said the number of refugees fleeing the fighting increased by nearly 100,000 in the past month. On Tuesday, a riot reportedly broke out in the Zaatari Syrian refugee camp in Jordan. Refugees attacked aid workers after the first winter storm in the camp caused torrential rains and winds that swept away tents. Nearly 50,000 people are housed in the Zaatari camp and they are becoming increasingly frustrated with conditions that one person called “worse than living in Syria.”

see Syria Comment